Additional information from Paul Butler, author of Orchids and Butterflies: The Life and Times of Theodore Mead; Hope Springs Eternal: A History of Mead Botanical Garden; and A Life Touched by Nature: A Biography of Jack Connery.

A small white egret, eyeing glassy pond water in search of silvery minnows, balances on a rock. Two gopher tortoises wrestle head-to-head in a slow-motion battle of wills. A bicyclist takes a break, peering up into an enormous pine tree from which comes a windborne tune.

These are the creatures of Winter Park’s Mead Botanical Garden—humans, birds, reptiles and fish—that have found relief and sustenance in its 48 acres of precious green space. Tucked behind a busy municipal tennis complex, railroad tracks, apartment buildings and homes, the garden is located on the south side of the city, bordered to the east by Pennsylvania Avenue and to the west by South Denning Drive.

But beyond its shady (and easy to miss) bricked entry, the garden offers calm amid chaos and an opportunity to experience a different kind of park—one that combines planted gardens with restored natural areas. It’s a quiet, verdant haven from harassment that allows the human spirit to rise while supporting natural habitats that have disappeared from much of Central Florida.

This ecological oasis—which is owned by the City of Winter Park and managed by Mead Botanical Garden Inc. (MBG), an independent nonprofit—is celebrating its 85th anniversary this year. Consequently, garden boosters are revisiting the roller-coaster history of “Winter Park’s Natural Place” while planning for major enhancements that the visionary founders (more about them later) would have loved.

Specifics are being codified in an ambitious new five-year strategic plan nearing completion with the support of the Washington, D.C.-based DeVos Institute for Arts and Nonprofit Management. (The DeVos family owns the NBA’s Orlando Magic.) “The plan is all about elevating the visitor experience,” says Executive Director Cynthia Hasenau, who adds that the garden welcomes about 70,000 people per year who picnic, birdwatch, meditate, practice yoga or explore aimlessly while soaking up the sights, sounds and scents.

Hasenau, who will retire this summer after 12 years at the helm of MBG, supervises a full-time staff of three: Emily Smith, programs and volunteer initiatives manager; Valerie Fetterolf, community engagement manager; and Olivia Brown, programs and social media coordinator. Phyllis Miller, the bookkeeper, is part-time.

The garden’s annual budget is only about $400,000, less than $100,000 of which comes from the city, with the rest raised through donations, activities, rentals and memberships. Volunteers—who have rescued the garden from neglect and natural disasters several times over the decades—provide about 8,000 hours of service annually. “An ideal budget would be about twice that amount,” says Tom McMacken, chair of the garden’s board of trustees, a retired landscape designer and a former city commissioner. “But I think it’s on our nickel to explain what we’re all about and earn the community’s support.”

That process is already well underway. Arguably the centerpiece of the proposed new slate of improvements will be a two-acre “Garden Within a Garden” that will enliven an unremarkable field northwest of the entrance on Garden Drive. That’s where the current greenhouse sits catty-cornered from a charming but modest alfresco wedding venue. The grassy expanse, known as the Legacy Garden, has admittedly not been the scene of much gardening apart from the carefully tended planted areas that surround the greenhouse.

That’s because, until recently, the space has been used for event parking. Handy, perhaps, but hardly ideal for horticultural endeavors. However, the strategic plan calls for the erstwhile parking lot to be blanketed by a collection of themed display gardens that will contain tropical, native, edible and flowering plants, and will connect the existing Camellia Garden and Yew Grove.

A state-of-the-art greenhouse will replace the current structure, which is home to the garden’s collection of orchids, ferns and various other botanicals. (The greenhouse is cultivated entirely by volunteers, some who simply enjoy gardening and others who have educational and professional backgrounds in horticulture.) “People love the natural landscape found throughout most of our property,” says Hasenau. “But this project will offer a much more cultivated, curated experience within a compact area. It will be inspirational and educational.”

Helping to design the Legacy Garden enhancement is Tres Fromme with Sanford-based 3. Fromme Design. Fromme’s extensive portfolio includes the Atlanta Botanical Garden, the Huntsville Botanical Garden and the Cheekwood Estate and Gardens in Nashville.

Also underway is a new pathway that will originate at the Legacy Garden, then meander through the Camellia Garden and around the north side of the stormwater marsh before it completes a quarter-mile loop back to its starting point. Existing trails, scenic though they may be, are mostly dirt (sometimes mulch) and replete with tripping hazards from jutting tree roots and cypress knobs. Not this one, which is being built by the city with accessibility in mind. It will be surfaced with crushed granite that’s traversable even for those in wheelchairs.

The city, in the meantime, is using a $2.2 million grant from the federal Natural Resources Conservation Services (NRCS) program to conduct the Howell Creek Stabilization Project, which will stem erosion, stabilize creek banks, remove sediment and restore native vegetation following significant damage from Hurricane Ian.

Howell Creek—which delineates the garden’s eastern edge—brings water from the wetlands near Orlando’s Spring Lake through Winter Park and into a lake system that eventually connects to the St. Johns River. The portion of the creek that runs through the garden—its longest uninterrupted stretch—provides an important habitat and travel avenue for wading birds, otters, turtles and fish.

During dry periods the creek almost disappears; during rainy periods it floods, demonstrating the fluctuations of natural systems and the importance of wetlands to the local ecology. “We want to restore the creek and to armor it against future hurricanes,” says Gloria Eby, director of the city’s Natural Resources & Sustainability Department.

Concurrently, another important project is being overseen by Eby. The long-closed (and hurricane-damaged) boardwalk through the garden’s wetlands will be restored by the city using a $500,000 grant from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection Recreational Trails Program.

The city was required to provide matching funds of $125,000 to receive the grant, which will enable work to begin this summer, according to Eby. She says that about 2,100 linear feet of boardwalk will likely be added, enabling garden visitors to explore previously all-but-impenetrable marshes that are dense with vegetation and abuzz with life.

These new initiatives will carry forward the momentum created by a slew of other improvements completed since 2020, including renovation of the Azalea Lodge—a popular events space that now also hosts a speaker series dubbed Life Explorer—construction of a new parking lot and expansion of the stage at the frilly Little Amphitheater.

Other projects completed since the pandemic have included the addition of a new picnic pavilion, replacement of a rickety creekside bridge and installation of a Native Plant Garden by the Tarflower Chapter of the Florida Native Plant Society.

In addition, the greenhouse has been upgraded and the Discovery Barn—home to an array of activities for youngsters, including an annual Young Naturalist Summer Camp—has been remodeled. (The camp, which typically hosts more than 500 children, quickly reaches capacity.)

Some projects were funded by the city, while others were paid from the coffers of MBG. “We don’t work in isolation,” says Hasenau. “We plan and coordinate with our city partners.” For example, she notes, the city and the garden recently split the cost of replacing the wind-battered canvas “sails” that flank the stage at The Grove.

A major capital campaign will soon get underway to raise funds for the projects envisioned in the strategic plan. McMacken figures that the organization will need to raise about $3 million over five years to complete everything on the wish list. “Just the greenhouse will be more than $1 million,” he says. “We’re going to do it in phases and stages as we’re able.” Not surprisingly, he adds, a major responsibility for the yet-to-be-chosen incoming executive director will be development.

But you may fairly wonder why such a place even exists in a city that has been built out for decades and where property values are stratospheric. The reason why there’s a patch of Old Florida wilderness in Central Florida’s most desirable and densely developed zip code is the sheer fortitude of Jack Connery, a Boy Scout, and Edwin Osgood Grover, a professor at Rollins College.

The Scout and the Prof

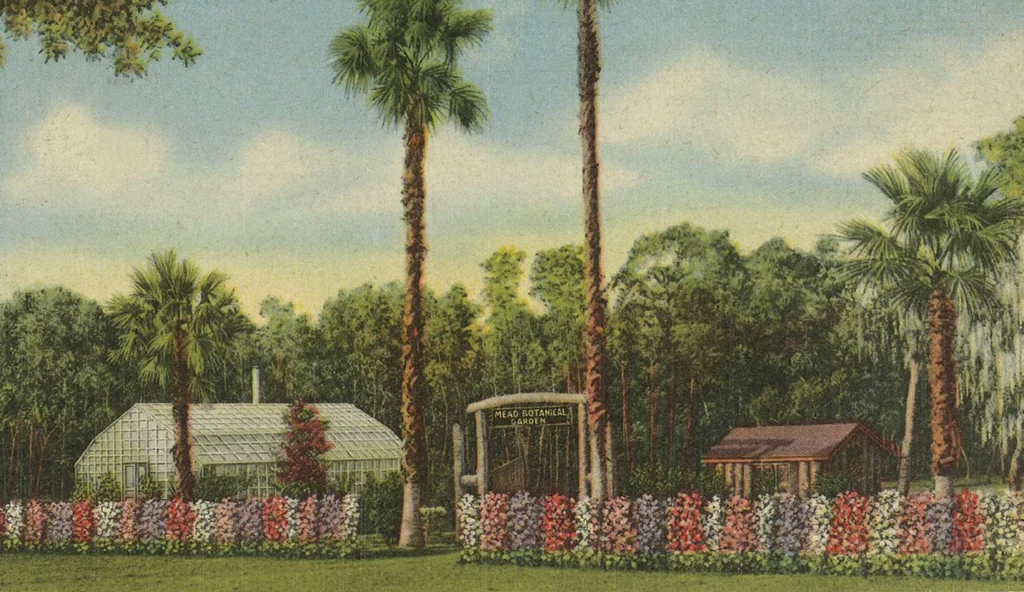

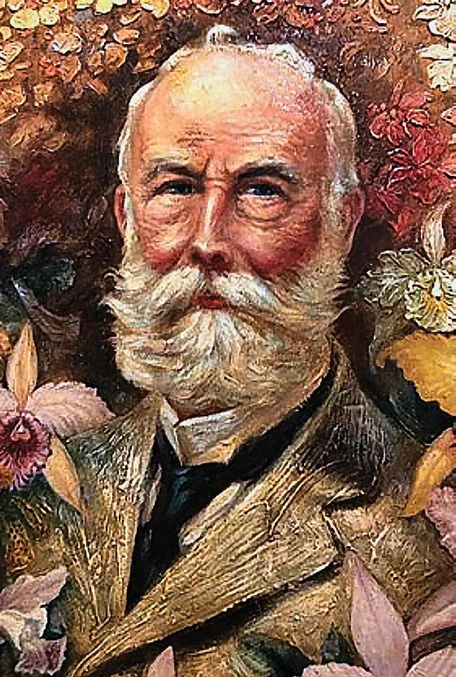

Mead Garden is named for Theodore Luqueer Mead, naturalist, entomologist and horticulturist who moved to Oviedo in the late 1880s. There, in an estate along Lake Charm, he grew exotic plants—particularly orchids—and became renowned for his hybridization techniques.

It was at a Boy Scout regional “camporee” at Silver Lake that Connery, an Eagle Scout, met Mead, the scoutmaster for a troop in Oviedo. An avid collector of birds’ eggs and nests, Connery soon became Mead’s protégé and helped the kindhearted scientist, then in his 70s, with crossbreeding experiments and the management of his gardens.

“Someday,” Connery told his mentor, “I am going to build a memorial garden for you.” Although undoubtedly flattered, the unassuming Mead could have had no idea that the enterprising young man—alongside a visionary professor—would eventually do just that.

Connery enrolled at Rollins in 1932 and met Grover, the whimsically titled “professor of books.” Coincidentally, Grover, too, was an admirer of Mead’s and had visited him several times in Oviedo. Grover’s brother, Frederick, was a professor of botany at Oberlin College and the siblings had, like Connery, pondered ways in which Mead’s orchids might be displayed and preserved for posterity.

When Mead, a widower with no children, died in 1936, he willed his massive collection of orchids, caladiums and amaryllis flowers and bulbs to Connery. Although Grover had initially tried to persuade Rollins to buy the Mead estate, the college wasn’t interested, thereby setting the stage for Grover and Connery to join forces and explore other ways to achieve their shared ambition of establishing a memorial garden.

But where would such a garden go and who would foot the bill? The “where” question was answered rather quickly. Near the college, it so happened, was a low-lying area along Howell Creek that Grover and Connery believed would be perfect for the venture.

Grover, who in an earlier life had sold textbooks and still knew how to close deals, persuaded the owners of various contiguous tracts to donate their properties to a newly formed nonprofit: Theodore L. Mead Botanical Garden Inc.

He immediately approached Walter W. Rose, a developer and state senator who owned 20 acres buffering his new subdivision, Beverly Shores. Undoubtedly, Rose reasoned, adjacency to a botanical garden instead of a swamp could only enhance the value of his homesites. Consequently his donation, generous as it appeared, surely benefited him as much as it did the garden.

A Jacksonville beauty operator, Mary Bartels, signed over more than 15 acres of inherited pineland that now encompasses the main entryway and the Legacy Garden. Her motives for doing so remain unknown, although—and this is pure speculation—it may have been for tax reasons.

James A. Treat, a former Winter Park mayor, contributed another six acres that included a heretofore hidden lake that he insisted be named “Lake Lillian” for an undoubtedly grateful granddaughter. Smaller parcels, including 1.9 acres owned by Orange County and used to extract clay for road-building projects, were secured and helped to complete the puzzle.

Now, with a site cobbled together, there remained considerable (and costly) work required to transform it into a garden. The tentative plan, as described by Grover and Connery, called for miles of shaded trails, greenhouses for exotic plants (including Mead’s), an arboretum for native and imported trees and shrubs, and an aviary that would allow visitors to study bird life in a seminatural setting. There would, hopefully, even be an outdoor marine aquarium.

As for Howell Creek, the duo proposed that it would be widened and deepened to create three large mirror pools strew with colorful day-blooming lilies. Each pool would have a waterfall that resulted from progressive downstream drops in elevation.

As for who would foot the bill, Grover—not surprisingly—had an idea. He persuaded the city to take temporary title to the property and to apply for a grant from the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA). The New Deal agency eventually approved $20,170 (the equivalent of about $450,000 today) to get the project started.

Inconveniently, however, the grant required that the city—which was already in default on $90,000 worth of municipal bonds—put up matching funds, which it didn’t have. This was, after all, in the midst of the Great Depression.

Connery, however, saved the day when he gave the city an assortment of palm trees and Mead’s plant collection, which was valued at more than $20,000. The WPA agreed to allow the city to donate the plants in lieu of putting up more cash.

But WPA money could only be used for labor, not materials. Which is why it was fortunate that influential Orlando Sentinel publisher Martin Andersen adopted the garden as a cause célèbre, publishing a series of beseeching editorials that generated about $11,000 (the equivalent of about $250,000 today) from readers.

In addition, Grover came up with the notion of issuing “revenue certificates” for materials purchases. The certificates—which came in increments of $25, $50 and $100—offered 2 percent interest per year and matured following 10 years, at which time they would (hopefully) be repaid from gate receipts (admission would be 25 cents, later raised to 50 cents). Many businesses gladly accepted the highly speculative certificates, including a local truck dealership when a heavy vehicle was needed to transport several hundred cabbage palms from Oviedo to Winter Park.

Mead Botanical Garden officially opened on January 15, 1940, in a formal ceremony that included local dignitaries, elected officials and 3,000 spectators—including 20 “hostesses” costumed as Cypress Gardens-style Southern Belles. The idea was, in fact, proffered by Dick Pope, founder of the iconic attraction that was known for its waterskiing shows and its photogenic antebellum beauties.

The straitlaced Grover couldn’t have been overjoyed at this. But Pope, the man already known as “Mr. Florida,” had volunteered his services as a public relations consultant and clearly knew how to run a successful garden attraction. As far as is known, Grover gritted his teeth and didn’t object to this exploitation of feminine pulchritude.

“What used to be a city dump is now a bond of beauty between Florida’s two finest cities, Orlando and Winter Park,” said one of the opening day speakers, Orlando Mayor Sam Y. Way. (A little more than two acres of the garden lies in Orlando, not in Winter Park, with a now-unmarked entrance in Beverly Shores.)

For years, the garden was indeed one of the most beautiful spots in Central Florida, and a fitting tribute to both the genius of Mead and the determination (and ingenuity) of Connery and Grover—who had, against all odds, managed to build a beacon of botany during a national economic calamity.

But 13 years later, the bloom was off the rose (or, more accurately, the orchid). In 1953, Theodore L. Mead Botanical Garden Inc., which was struggling financially, proposed that the city take over ownership and operational control of the garden.

The city agreed, but only on the condition that the garden’s creditors, many of whom had dutifully purchased revenue certificates, waive their claims to repayment. In addition, the city proposed to build a recreation center on the site that would include a youth center, a swimming pool, two baseball diamonds, a football field, two volleyball courts and four tennis courts. It had also been proposed that a new county elementary school be built on the site.

Certain garden elements would be preserved and enhanced, but the overall plan was still a far cry from what had been envisioned by Grover and Connery. Yet the cash-strapped nonprofit had no choice but to capitulate or see the garden close entirely. Consequently, by 1955, the city owned and operated the property and placed it under the auspices of the Parks Board, precursor to today’s Parks & Recreation Advisory Board.

In the coming years, however, nothing happened. The garden gradually became a mishmash of elements, among them maintenance sheds for city vehicles and a dumping ground for construction detritus. The greenhouses that had sheltered Mead’s flowers fell into ruin and were eventually demolished, while his collection and other botanicals (those that hadn’t already died, at least) were spirited away by parties unknown.

Decades after its creation, the vision articulated by Grover and Connery had been forgotten—or, more likely, ignored. Grover decried the situation, and relentlessly sought solutions, until his death in 1965 at age 95. Connery and his wife, Helen, eventually threw up their hands and decamped to DeLand, where they started a successful landscaping business that they operated until his death in 1982 at age 74.

For the next several decades, maintenance consisted of mowing over native plants, leaving them unable to naturally grow and reseed. Non-native trees, plants and vines overwhelmed the wetlands. Wooden boardwalks were built and then abandoned to rot. The garden, it seemed, had become an anachronism in a city known for its posh shopping district and its luxurious lakeside mansions.

Something needed to be done but no one, it seemed, could agree on exactly what. In 1988, Mayor David Johnson appointed a 15-member Mead Garden Task Force, which recruited the Orlando Chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects to assist in formulating a comeback strategy. Predictably, perhaps, the plan gathered dust.

In 1992, a Rollins class analyzed the site, offering a vision for a boardwalk system that included signage to educate visitors about local ecology. Again, nothing of consequence resulted.

Despite fits and starts of ideas and activity, a comprehensive management structure and adequate funding for restoration never materialized. The garden needed new energy to replicate the commitment of its early champions like Grover and Connery.

Enter the Friends of Mead Garden, a nonprofit formed in 2003. The grassroots (pardon the pun) group of concerned citizens, founded by Beverly Lassiter, president of the Winter Park Garden Club, organized volunteers for cleanup duty and advocated improvement plans to city officials. “Where some saw vines and neglect,” says Hasenau, “Beverly saw possibility and beauty.”

Lassiter and other volunteers remained undaunted even following the terrible trifecta of hurricanes in 2004. Charley, Frances and Jeanne—three massive storms in six weeks—left the wetlands a mess and blew in more invasive species.

The Friends, however, never relented and likely felt some vindication in 2007, when the city approved a strategic plan for garden restoration presented by Post, Buckley, Schuh & Jernigan, a large architecture and engineering firm. But an economic storm—this time the Great Recession—caused funding for reclamation to be slashed. Still, volunteer “Weed Warriors” and “Butterfly Brigades” soldiered on, mostly on weekends, doing what they could with limited resources and motivated by the righteousness of their cause. Gradually, thanks largely to these vehement volunteers, locals began to rediscover the natural oasis literally in their own backyards.

In 2012, The Grove—an amphitheater that’s home to the Florida Symphony Youth Orchestra—was built for about $700,000, with an anonymous donor contributing $250,000, the city allocating $200,000, and the rest raised from individuals, organizations and foundations.

That same year, the Friends of Mead Garden—now Mead Botanical Garden Inc. (MBG)—signed a multiyear agreement with the city that essentially turned over operational responsibility to the privately funded organization and its 16-member board. It also hired Hasenau, a former director of management and executive education at Rollins’s Crummer School of Business, as executive director.

That same management and ownership structure remains in place today, and Mead Garden—which began with such promise—has over the past decade or so been revitalized in a way that would have pleased Grover and Connery.

Mead himself, although he would have insisted that he was undeserving of such an honor, would surely have been heartened that, in its time of need, the garden named in his honor was rescued by everyday people who loved nature as he did.

According to Hasenau, as part of the garden’s continuing anniversary commemoration, the staff is collecting testimonials and memories to be used in a yet-to-be-determined tribute. To share your memories and photos, send them to info@meadgarden.org.

In Brief

Mead Botanical Garden is open daily from 7:30 a.m. to dusk. It’s located north of Orlando, just off U.S. 17-92 in Winter Park. Coming from Orlando, turn right (east) onto Garden Drive just past the Winter Park city limits. Coming from Winter Park, turn left (east) onto Garden Drive, just past Orange Avenue. Garden Drive leads directly to the main entrance. In addition to being a beautifully unspoiled nature area, the garden boasts a number of facilities available for public use.

Among them:

THE GROVE. This multipurpose, open-air venue hosts an array of musical and theatrical productions. It’s a great place to bring a blanket or a lawn chair and watch a performance in the glorious outdoors.

THE LITTLE AMPHITHEATER. Built in 1960, the Little Amphitheater has for decades been one of the most popular settings in the region for weddings and other special functions. Outdoor bench seating can accommodate up to 300 people.

PICNIC PAVILION. Looking for a place to hold a picnic, family birthday party or class reunion? The newest pavilion, located near the main entrance next to the parking lot, offers a shady setting and several tables.

THE AZALEA LODGE. This recently remodeled facility is the perfect indoor space for special events. The 2,400-square-foot reception hall, which has a capacity of 175, includes a foyer, a meeting space and a main hall. An outdoor terrace overlooks Alice’s Pond.

THE LEGACY GARDEN WEDDING VENUE. Near the greenhouse is a small wedding venue shaded by massive live oak trees. Plans call for the area around it to be planted with a variety of curated display gardens.

Mead Botanical Garden also has a community vegetable garden, a popular summer camp, a speaker series, birdwatching expeditions, guided hikes, a fall plant sale and such events as the annual Great Duck Derby—the racing ducks are of the rubber variety—which supports the garden’s educational programs. For more information, call 407.644.6362 or visit meadgarden.org.