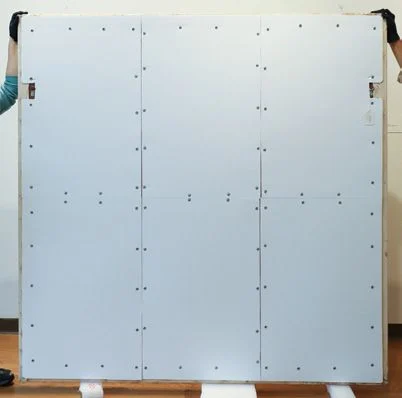

The canvas of Always by Suzanne McClelland showed signs of expansion and contraction. So conservator Stephanie Conforti equipped the work with a backing of corrugated plastic layered with polyester batting. | Courtesy Orlando Museum of Art

As visitors entered Relationships: A Love of Collecting, a recent Orlando Museum of Art exhibition, they were likely struck by the large and prominently placed painting Always, by acclaimed abstract artist Suzanne McClelland. There was no hint that, before its installation, trouble loomed for the stunning work. The 72-by-72-inch canvas was under stress from clay elements applied primarily atop acrylic paint. Every movement of the work endangered the adhesion of the clay. Always clearly needed treatment to guarantee that it could be preserved in its present condition.

Relationships—on view at OMA through May 15—was the first exhibition of works gifted to the museum by New York collectors James Cottrell and Joseph Lovett. In assessing this first shipment from the 314 donated pieces, Chief Curator Coralie Claeysen-Gleyzon looked not only at their content but also their stability.

“We are stewards of that collection,” says Claeysen-Gleyzon. “When we acquire a piece, we need to bear in mind that we need to care for it for posterity.” Thankfully, most of the art was in pristine condition, but three pieces—including McClelland’s Always—required attention.

Conservation of contemporary art, a focus at OMA, presents unique challenges because of unconventional materials. On Always, for example, the back of the canvas already showed signs of expansion and contraction. So, OMA sought the expertise of Orlando painting conservator Stephanie Conforti, who equipped the painting with a backing board of corrugated plastic layered with polyester batting.

“The backing board is a way of reducing canvas movement and reducing future cracking and/or loss,” says Conforti. But could she clean the piece? No. The media that McClelland used included charcoal, a loose pigment, and there is no way to tell the difference between charcoal and dust or grime. Her work on Always and several other pieces in the exhibition amounted to preventative care, adds Conforti.

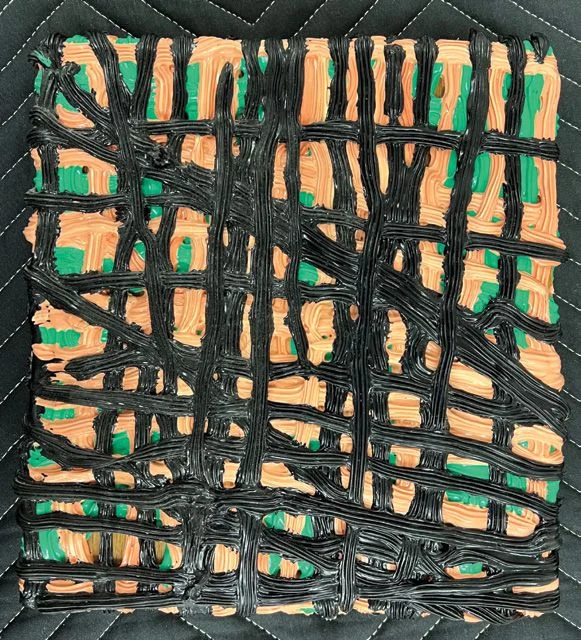

The thick layers of an untitled acrylic-on-wood work by French artist Dominique Figarella were a magnet for dust, which over time could seep into the pigment and cause discoloring. Conforti used Q-Tip-like swabs to bring the work back to its original vibrancy. | Courtesy Orlando Museum of Art

One untitled acrylic-on-wood work by French artist Dominique Figarella, however, could be cleaned, despite the fact that the object’s thick layers made it a magnet for dust—which over time can seep into the pigment. Because the solubility of every painted surface has a different tolerance, Conforti conducted tests and customized a water-based solution for accomplishing the task at hand. Using her own Q-Tip-like swabs made of rolled cotton and wooden skewers, it took her five hours to bring Figarella’s work back to its original vibrancy.

An art conservator’s rare specialty requires a knowledge of fine art, art history and, of course, science. Painting from the 19th century through the mid-20th century was more formulaic, says Conforti, and artists were well trained in materials and techniques. Today, however, just about anything goes. Conservators like Conforti often wish that contemporary artists had more knowledge about the stability of the materials and media in which they choose to work. “With contemporary art,” she says, “it is much more about the artistic process.”

Conforti holds a master’s degree in art conservation from SUNY Buffalo State University in New York—one of only three universities in the country to offer such a degree—and a bachelor’s degree in fine art from Parsons School of Design/The New School in New York City.

Her elite education also includes two years of classes and a one-year internship at the Carnegie Museum of Art and The Andy Warhol Museum, both in Pittsburgh. Even so, not every eventuality can be anticipated in a classroom—particularly where the peculiarities of contemporary art are concerned.

The centerpiece of French artist Philippe Mayaux’s three-piece work Genius needed a new lightbulb.The tiny bulb was found easily enough but it was unclear how it was originally lit. Conforti worked with an electrician, not an artist to devise a solution. | Courtesy Orlando Museum of Art

In her third assignment for Relationships, Conforti applied her sensitivity to the care of acrylic and oil paints—as well as some common sense—for French artist Philippe Mayaux’s three-piece work Genius, which needed a new light bulb. But making it work wasn’t as easy as it sounds.

The centerpiece of the grouping, created in 1990 and 1991, features a tiny flashlight-sized light. The bulb was found easily enough through retail sources, but it was unclear how it was originally lit for exhibition. So Conforti worked with an electrician, not an artist, to devise a solution.

A battery pack wasn’t a good option. When the batteries died, the piece would have to been removed from the wall and the batteries replaced. But by running an electrical cable through the wall to a switch, OMA staffers could turn on the light when the facility opened and turn it off when it closed.

“It was important that the electric system be safe, the object was minimally handled, and the switch be away from the object,” says Conforti, who presented a talk to OMA members this winter about conservation and the sometimes-unexpected challenges that conservators face.

In OMA’s extensive contemporary art collection, visitors see all manner of media—twigs applied to a painting, a dress made of paper, a top-heavy sculpture with ceramic birds encircling a gramophone. With the right care, these objects will be enjoyed for many years to come.

“Conservation is ongoing,” notes Claeysen-Gleyzon. “We are constantly monitoring the works in our vaults.”

Orlando Museum of Art is located at 2416 North Mills Avenue, Orlando, in Loch Haven Cultural Park. For more information, call 407.896.4231.