It has been a weird couple of decades. We’ve had a major recession, a global pandemic and, more recently, political polarization unlike anything experienced in our lifetimes. But, as always, the arts have given us hope, fueled our optimism and helped us cope (if only for a few hours at a time) with what we’ve just heard on the evening news or read on our social media platforms. So it’s more important now than ever before that we celebrate the people and the organizations who bring us joy and remind us of what’s best about being human: the ability to imagine and create. This year, some of the most significant arts organizations in Central Florida are marking milestones that range from a decade to a century. Let’s collectively wish them all happy birthdays by supporting their missions and helping them thrive until the next milestones come around.

100

Orlando Family Stage

On February 3, 1926, a troupe of stagestruck locals—alongside student members of the Little Theater Workshop at Rollins College—presented four one-act plays before a packed house at the Beacham Theatre in Downtown Orlando. The first production from the Orlando Little Theatre Players may not have been exceptionally polished but it was, according to the Orlando Sentinel, “well balanced from beginning to end and without a dull moment.”

Under the direction of Orpha Pope Grey, the college’s dramatic coach, students starred in Everybody’s Husband and The Camberley Triangle, while community members—friends and neighbors—starred in The Valiant and Thank You, Doctor. Newspaper advertisements leading up to opening night had simply promised “four good one-act plays.” That bar appears to have been comfortably cleared.

Although several of these plays were popular at the time, none—with the possible exception of The Valiant—is still performed a century later. But the Orlando Little Theatre Players (which was founded in 1925, hence this year’s anniversary celebration) is still around and stronger than ever in its eighth iteration as Orlando Family Stage.

Chris Brown, executive director, has been affiliated with the theater for 15 years as production manager, general manager and interim executive director before the “interim” was dropped from his title in 2019. “I don’t want to be in the spotlight,” says Brown. “My comfort is being backstage and pulling the rope that no one sees, you know? I try to take this mindset into my role as executive director.”

Brown, who holds a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from UCF and an MFA in technical design and production from the Yale School of Drama (now the David Geffen School of Drama at Yale University), notes that the theater, whatever its moniker, “has always had an affinity for children’s programming.”

Still, no Roaring Twenties founders could have guessed that their itinerant institution—which had no venue of its own until 1959—would become a nationally renowned mecca for youthful creativity and expression and a leading-edge theatrical education innovator.

Since 2000, in fact, Orlando Family Stage has partnered with the University of Central Florida to host a Master of Fine Arts program in Theater for Young Audiences (TYA)—making UCF’s the only TYA master’s program in the state (and perhaps the country) that offers affiliation with a professional theater.

But how did this evolution occur? A (not-so) brief examination of the theater’s history reveals an institution that survived booms and busts and at times struggled to find a niche. The original effort, inspired by the “little theater” movement that swept the country following World War I, was a project of the City of Orlando Recreation Department.

For years, plays were held mostly in school auditoriums, civic club halls and, for a time, a chapel at the old Orlando Army Air Force Base (later the Orlando Naval Training Center and now Baldwin Park.) Early seasons usually encompassed eight to 10 plays—usually proven crowd pleasers—that were presented wherever a stage could be secured.

In 1934, the theater dropped the word “Players” and filed for incorporation as the slightly simplified Orlando Little Theatre. That year, Martin Flavin’s Broken Dishes, staged at Sorosis House, proved to be such a hit that it encored the following year at the Orlando Municipal Auditorium (later the Bob Carr Theater) and sold some 3,000 tickets.

What was all the fuss about? The play, which premiered on Broadway in 1930, was apparently quite funny. It had been a big hit and served as the foundation for a film adaptation, Too Young to Marry, in 1930. But, well-received shows aside, the theater was inactive from 1942 to 1946 because of World War II.

When it reemerged in 1946, lying in wait was a splinter group of former participants calling itself the Community Players. The feuding groups negotiated a truce, merged operations, and the Orlando Little Theatre became the Orlando Players in 1953. Drama among theater organizations? Who would have thought it possible?

Among the theater’s greatest hits of the 1950s: The Bad Seed, presented in 1957 at the Syrian-Lebanese American Club and directed by Peter Dearing, a theater professor at Rollins. Dearing cast precocious Anne Hathaway, 11, who was said to have chewed up the scenery as pigtailed psychopath Rhoda Penmark.

In 1959, according to Orlando Sentinel columnist Jean Yothers, the name was changed yet again—to the Orlando Players Little Theatre—because “local yokels thought ‘Orlando Players’ was a ball club.” (In truth, the local yokels made a valid point.)

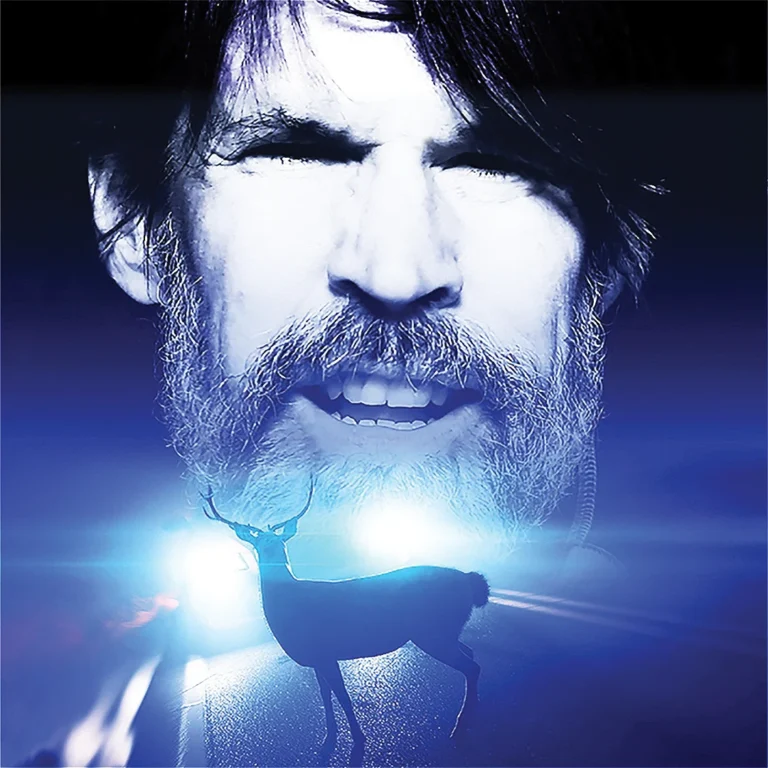

In 1959, the Orlando Players Little Theatre bought a bungalow at 813 Montana Avenue—now the Vajrapani Kadampa Buddhist Center—and converted it into a 124-seat venue. Although this location was intended to be temporary, it would be another 14 years before the theater—now Orlando Family Stage—would move into a proper facility at Loch Haven Cultural Park. | Courtesy Orlando Family Stage

That same year, the theater bought a modest bungalow at 813 Montana Avenue (now the Vajrapani Kadampa Buddhist Center) and converted it into a 124-seat venue. Surely, though, this was a short-term situation. Indeed, the city had already designated a site for a new theater in Loch Haven Cultural Park. Board members had even broken ground and installed a sign that read “Help Us Grow.”

So the humble frame house—where dressing rooms and scenery storage were in the garage—was meant to be used only until funds could be secured for a proper facility within the city’s emerging 14-acre cultural campus that abutted Orlando Avenue. As it happened, however, the all-too-literal “little theater” building would have to suffice for the next 14 years.

On October 14, 1959, John Van Druten’s Old Acquaintance—a frothy comedy that had enjoyed a Broadway run in 1940 and had been adapted into a film starring Bette Davis the following year—became the first production staged at Montana Avenue and opened a six-show season under the energetic leadership of its new president, Evelyn Cole Duclos, a cultured and cosmopolitan clubwoman who lived in Winter Park.

(Duclos, who died in 1976 at age 85, served as president until 1965 and was president emeritus when the new theater was finally built. A former prep-school drama teacher, she had written a play, Mouth of the Gift Horse, that was staged in 1975 at the Winter Park Women’s Club and starred Orlando native and Miss Florida of 1974 Delta Burke.)

Generally, the theater’s offerings in the coming years were well-reviewed—especially by the Orlando Sentinel’s Sumner Rand, who also acted in several productions. At times, though, the box office was juiced by augmenting local talent with such dimming stars as Claire Luce, Julie Haydon and Harry Blackstone Jr.

In 1960, children’s summer programs began and, later, acting classes were offered for children and adults. Children were taught by Howard Davis, who had acted in numerous local productions and was a teacher at Union Park Junior High School. Adults were taught by Ginny Cortez and Sara Daspin, who would become icons in the local theater community as actors and directors.

But let’s face it—you can only do so much at a location like Montana Avenue. The theater’s name was changed again in 1968, to the Central Florida Civic Theatre, and boosters renewed their push to raise money and move to Loch Haven Cultural Park. A $275,000 fundraising effort was initiated in 1969—but the goal would steadily be revised upward over the span of several years.

Respected journalist Joseph L. Brechner—a former president of the theater’s board and a founder of Orlando ABC affiliate WFTV-Channel 9—kicked off the campaign with a thoughtful opinion piece in the Orlando Sentinel encouraging financial support and asking: “What role will you play?” Public support for the effort was strong.

And, luckily for the theater, it had another influential fan in Edyth Bassler Bush, a former actress and wife of 3M founder Archibald Granville Bush. Though she never had children of her own, the colorful Mrs. Bush was passionate about involving young people in the arts—first in St. Paul, Minnesota, and later in her adopted hometown of Winter Park.

“She believed that theater instilled skills that benefited children personally and, as adults, professionally,” says David Odahowski, president and CEO of the Edyth Bush Foundation. “Following her passing in 1972, the foundation sought a meaningful way to honor her legacy.”

Ground was broken for the theater—which ultimately cost more than $450,000—on April 18, 1972. Mrs. Bush’s legacy was so significant that the building’s 330-seat proscenium-style auditorium was named, and remains named, the Edyth Bush Theatre. The benefactor—a woman whose name remains synonymous locally with philanthropy—died just six months later.

(Tupperware Children’s Theatre, named for a familiar corporate donor, opened in 1975. It became a black-box space when the Ann Giles Densch Theatre for Young People opened.)

The first show at the brand-new Civic Theatre, on October 18, 1973, was a gala preview for donors of Butterflies Are Free, which featured TV and Broadway star Julia Meade. The rest of the season included Anything Goes, The Lion in Winter, Our Town, Arsenic and Old Lace and The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds.

All were sellouts well in advance; the theater had notched some 1,500 season ticket holders fully four months before opening its doors. (There had been 410 season ticketholders at Montana Avenue.) But seemingly insurmountable financial challenges were yet to come.

The Civic Theatre began to slide into a fiscal crisis in the 1990s as newer theaters began to erode its audience and divide its donors. “Nobody has been sure what kind of theater the company has been trying to be,” wrote critic Elizabeth Maupin in the Orlando Sentinel. “And the kind it used to be, a small-town theater with amateur actors, no longer works in a community as expansive and diverse as Orlando.”

Staff resignations and a complete turnover of the board of directors finally led to a just-in-the-nick-of-time merger with the theater department of UCF’s College of Arts and Sciences, which needed a home for a proposed MFA program. Added Maupin: “For UCF, the merger plan means a much-needed next step in its aim to train master’s-level theater students to become theater professionals.”

(To elaborate: The theater assigned its land lease with the city to UCF, which in turn made $2 million in repairs to the building and entered into an agreement with the theater that allowed it to continue operating and managing the facility. Before any of this could happen, private donors had to pay off a debt load of $340,000.)

Although some local theater aficionados feared that their still-beloved community playhouse would become an academic unit of the university and lose its hometown focus, their concerns proved unfounded. A generic placeholder name was chosen: the UCF Civic Theatre, which two years later became the Orlando Repertory Theatre.

The Rep, as the operation was then colloquially known, became fully integrated with UCF’s MFA program, which had expanded its focus to embrace TYA. Many students—who collaborated with professional artists, technicians and administrators—graduated from the program and were quickly hired as executives of other nonprofit youth-oriented theaters around the country.

“I get calls all the time from professional theaters looking to hire our graduates,” says Jeff Revels, who joined the organization in 1995 as a box office assistant, then became education director and was appointed artistic director in 2006. “We have people [working] at places like Lincoln Center and the Kennedy Center.”

So thoroughly joined at the hip are the theater and the university’s theater program that some Orlando Family Stage employees are also adjunct faculty members at UCF: Brown, the executive director; Tara Kromer, the props manager; and Emily Freeman, the senior director of development.

Chris Brown, executive director, has been affiliated with the theater for 15 years as production manager, general manager and interim executive director before the “interim” was dropped from his title in 2019. Jeff Revels, who joined the organization in 1995 as a box office assistant, then became education director and was appointed artistic director in 2006. | Courtesy Orlando Family Stage

In 2023, following in-depth market research, the Rep changed its name to Orlando Family Stage to better reflect its exclusive focus. The new handle didn’t indicate a change of direction—the theater was never, by definition, a repertory theater—as much as it affirmed the existing mission: “Empowering young people to be brave and empathetic through quality theatrical productions.”

In addition to its seasonal productions, that lofty goal is reinforced by such successful programs as the Youth Academy, which offers classes and workshops, and Theater for the Very Young, which offers immersive experiences for early learners such as Baby & Me and Toddler Story Strolls.

During its 100th anniversary season, Orlando Family Stage—which has a $4 million annual operating budget—plans to focus on enhancing the guest experience with physical plant upgrades, both cosmetic and functional, funded by a $4 million grant from Orange County’s Tourist Development Tax.

It will also bolster fundraising through its “100 Seats for 100 Years” program, in which donors—corporate and individual—will be solicited to invest $2,500 each to provide theater experiences for 100 children. That would be a 60 percent increase over last year’s effort.

On stage, the 2025-26 season will feature stage adaptations of children’s books. The seven shows, including five musicals, will begin with the multilingual Go, Dog. Go! (Ve Perro ᴉ Ve!), which will run from September 4 to October 3, followed by Goosebumps The Musical: Phantom of the Auditorium (September 29 to October 31) and Pip-Squeek: An Anti-Bullying Magic Show (October 14 to 17).

The reading enrichment theme—chosen partly as a response to falling test scores as a lingering result of COVID-19—will be bolstered by the inaugural Florida Children’s Book Festival, which will run from February 20 to 22, 2026. Held in partnership with Writer’s Block Bookstore in Winter Park, the festival will feature storytime readings, author signings, character meet-and-greets and more.

In addition, the Edyth Bush Charitable Foundation—perhaps the theater’s most important patron over the decades—has announced a $500,000 grant to support the book festival and various other activities during a vibrant and inclusive two-year celebration of the theater’s centennial.

“Reaching 100 years is more than a milestone—it’s a testament to the power of storytelling, education and the arts to unite and inspire,” says the foundation’s Odahowski.

He continues: “Orlando Family Stage has nurtured creativity, sparked imagination, and built community for a century. We’re honored to support its celebration and ensure its legacy continues to thrive. It has not only stood the test of time—it has helped shape the cultural identity of our region.”

Orlando Family Stage is located at 1001 East Princeton Street, Orlando, in (finally!) Loch Haven Cultural Park. For more information, call 407.896.7365, or visit orlandofamilystage.com.

50

Crealdé School Of Art

Visiting Crealdé School of Art’s campus is akin to visiting a different world, with low-slung warrens of studios, classrooms, an outdoor sculpture garden and two galleries. In addition to the school, Crealdé also operates the Hannibal Square Heritage Center on the traditionally African American west side of Winter Park. At that facility, which opened in 2007, you’re greeted by a life-sized statue of the late Richard Hall, a Hannibal Square native and veteran of the famed Tuskegee Airmen. | Courtesy Crealdé School of Art

William S. “Bill” Jenkins made his fortune building solid, inexpensive homes throughout Central Florida. But the Georgia native certainly had the soul of an artist—and no small amount of talent as a painter. Art, believed Jenkins, was for everyone, regardless of social stature or skill level.

And he made certain that, in Winter Park at least, anybody seeking a creative outlet had one. In fact, “Art Is for Everyone” remains the motto at Crealdé School of Art as it celebrates its 50th anniversary.

“This is a creative hub that inspires person growth and personal connection,” says CEO and Executive Director Emily Bourmas-Fry, who came to the school in 2024 after serving as director of development and director of marketing at Orlando Museum of Art.

She began her tenure as Peter Schreyer entered the final months of his 30-year helm of the organization. The documentary photographer retired in January 2025. During Schreyer’s tenure, the school’s annual budget increased from $275,000 to $1.5 million, and its programs have grown from serving several hundred to more than 4,000 students annually.

Bourmas-Fry earned a master’s degree in cultural anthropology from the University of Adelaide, Australia. She is bilingual (English and Greek) and holds citizenships in Greece—where her family is from—as well as in Australia and the United States.

“Even after all these years, this campus still feels like a sanctuary for visual art—one of Florida’s true cultural treasures,” says Bourmas-Fry of Crealdé, tucked alongside a small lake (well, a pond really) and obscured by strip shopping centers that line busy Aloma Avenue. “It’s a place for freeing yourself without feeling intimidated. After all, everybody is an artist.”

Bourmas-Fry, in fact, plays the cello and likes to paint (mostly still-life images in acrylics, although a class she took at the school has steered her toward experimenting with abstracts). Her artistically inclined 11-year-old twin daughters also take a variety of classes at Crealdé.

Visiting the site is indeed akin to visiting a different world, with low-slung warrens of studios, classrooms, an outdoor sculpture garden and two galleries: the Showalter Hughes Community Gallery and the Alice & William Jenkins Gallery. Not surprisingly in a setting like this, something special happens for many people almost every day at Crealdé.

More than 125 classes and workshops for adults and children cover a wide range of visual arts disciplines: ceramics, fiber art and jewelry making as well as drawing, painting, photography and sculpture. The 90-person faculty consists of professionals who work in the art forms that they teach.

In addition to the main campus, Crealdé also operates the Hannibal Square Heritage Center, located on the historically African American west side of Winter Park. That facility, which opened in 2007, was founded by a partnership involving the school, a cadre of west side citizens and the city’s Community Redevelopment Agency.

The center‘s cornerstone exhibition, The Heritage Collection, includes archival photographs dating back to the 1880s and fascinating oral histories from many of the neighborhood’s long-time residents. A timeline documents significant local and national events in African American history since the Emancipation Proclamation.

Crealdé also has a satellite location in Winter Garden at the Jessie Brock Community Center. Among its most notable projects there: The Last Harvest: A History and Tribute to the Life and Work of the Farmworkers on Lake Apopka, a multimedia exhibition in partnership with the Farm Workers Association of Florida and the Winter Garden Heritage Foundation.

It is said that Jenkins devised the name “Crealdé” by combining the Spanish word crear (“to create”) and the Old English word alde (“village”). Born in rural Preston, Georgia, in 1909, he told the Orlando Sentinel in 1988 that he was inspired to found the school by childhood memories of quilting bees.

“When the other kids were sick or busy, I didn’t have much to do,” recalled Jenkins. “So I would go to the quilting bees and listen to the ladies talk as they worked. They had the best time, and so did I.’’

Crealdé, added Jenkins, was in part an effort to re-create that sense of community and creativity. He also wanted to foster an environment where artists—and, more importantly, would-be artists—could learn from their instructors and from one another in a welcoming environment.

“My father wanted to make certain that everyone had access to making art,” says daughter Ann Jenkins Clement. “He loved children’s art, especially. We had it all over the house when I was growing up. Most of all, his goal was to make sure that people who were interested in art were encouraged to give it a try.”

Jenkins earned a BFA from the University of Florida in Gainesville and traveled to Italy, where he graduated from the Royal Academy of Fine Art in Florence. He married Alice Moberg in 1942 and served in the U.S. Army during World War II.

Before Jenkins started his homebuilding business, he worked with the Veterans Administration in St. Petersburg and Tallahassee to develop a pioneering art therapy program for returning GIs. Says Clement: “My dad was a big believer in the beauty of art, but was also convinced that creating art could aid in emotional healing for the soldiers.”

Later, as his homebuilding company grew to become one of the largest in the region, Jenkins continued to paint for pleasure and decided to develop his long-dreamed-of complex for artists as a private enterprise. But that organizational structure proved difficult to sustain.

So in 1981, he reorganized Crealdé Arts Inc. as a nonprofit, which opened up new sources of funding. Ten years later, he donated the entire facility—with land and buildings worth some $750,000—to the nonprofit. This generous gesture helped to quell a mistaken perception that the campus was affiliated with the surrounding commercial development and was still a for-profit venture.

In recent years, the school celebrated the completion of a $425,000 renovation that created five new teaching studios. In addition to grants and donations, Winter Park-based construction company E2—whose owner, Rob Smith, attended the school’s summer art camp as a child—contributed $200,000 worth of in-kind support and materials.

A new woodworking and metal-smithing studio is also on the drawing board thanks to the generosity of William “Bill” Platt, a former board member and long-time supporter of Crealdé. Timeline details were being finalized at press time.

To celebrate its anniversary, Crealdé has slated its 50th Anniversary Exhibition to run from October 24 to January 25, 2026, in the Showalter Hughes Community Gallery. The exhibition, curated by Barbara Tiffany, will feature a selection of works by current and former faculty in a variety of mediums.

Alongside the artwork there’ll be archival photographs, publications and historical documentation that will trace Crealdé’s evolution from its founding in 1975 to its current role as a nationally recognized center for community-based arts education.

Jenkins would be proud of it all, according to his daughter. “My dad would have been so happy with how it has all turned out,” says Clement, who still takes painting classes at the school. “There’s such a feeling of community here. That’s what he was looking to create.”

He would also be pleased about the Heritage Center—which he didn’t live to see—because he built many affordable homes on the west side and came to love the community and its people, adds Clement.

Bourmas-Fry, discussing her goals for the school, says she wants to continue building on its already robust outreach initiatives and to initiate programs that explore the intersection of art and wellness—an affirmation of the founder’s strongly held beliefs about the healing power of creative expression.

“We’re enormously blessed to be headquartered in Winter Park,” says Bourmas-Fry, whose husband, Loren Fry, is a voice actor. “It speaks volumes that there are so many arts and cultural amenities, including Crealdé, where you can bring the family and where every voice matters.”

Crealdé’s main location is at 600 St. Andrews Boulevard, Winter Park. For more information, call 407.671.1886 or visit crealde.org. The Hannibal Square Heritage Center is located at 642 West New England Avenue, Winter Park. For more information, call 407.539.2680.

The Jesse Brock Community Center, where programs are offered in Winter Garden, is at 310 North Dillard Street, Winter Garden. Information about this branch location is available by calling or visiting the website for the main campus.

25

Downtown Arts District

The Downtown Arts District’s headquarters since 2018 is the Rogers-Kiene Building. Built in 1888, it is the oldest commercial structure in Orlando and also encompasses CityArts. DAD’s prior home base was at Orange Avenue and East Pine Street on the first floor of a historic movie house, which can be seen along the left-hand side of this archival image of Orange Avenue. The Phillips Theater, built in 1916, later became a drugstore and a nightclub before the DAD remodeled the space and moved into the first floor in 2006. | Courtesy Downtown Arts District

Orlando’s Downtown Arts District can trace its roots to 1997, when the more genre-specific Florida Theater Alliance was formed as the result of an Orlando Sentinel column by Elizabeth Maupin, the newspaper’s influential theater critic.

Wow! Who knew that newspaper columnists, not bloggers or podcasters, could be such movers and shakers? Those were the days, my friends. Maupin first addressed the idea in November of that year with a story about the Orlando-UCF Shakespeare Festival, whose venue-hopping made its performances a challenge to find.

Several paragraphs later, Maupin launched into a full-fledged lament about other local theater companies with no stages of their own: “Put those two factors together—homeless theaters and empty buildings—and a lively downtown theater district could be born.”

The column made the creation of such a district a cause in the arts community. In December, the Sentinel hosted a meeting attended by more than 150 representatives of theater groups and their supporters to get the ball rolling.

By 2000 the city had designated an official downtown arts district as being defined by Washington Street on the north, East Anderson Street on the south, South Rosalind Avenue on the east and Garland Avenue on the west. That same year, it had become apparent to some organizers that a more expansive effort, which would encompass all cultural attractions in addition to theaters, was needed.

So, with Orlando Mayor Glenda Hood’s blessing—and the promise of staff support from the city—the Downtown Arts District (DAD) split from the original performing-arts organization (which later became the Arts & Culture Alliance of Central Florida) and formed its own nonprofit.

DAD celebrated its debut with a high-profile event: “Art on (and off) Orange.” The purpose was a ribbon-cutting for OVAL (Orlando Visual Arts League) Gallery & Studios, which the organization had helped to subsidize. But there were also art exhibitions and live music performances throughout downtown in anticipation of an arts renaissance in the City Beautiful.

OVAL, at Orange Avenue and East Pine Street, occupied the first floor of a historic movie house turned drugstore turned rowdy nightclub (remember Bar Orlando?), which was built as the Phillips Theater in 1916 and became the Ritz Theater in 1929. The future looked promising indeed. Then reality set in.

By 2006, the gallery had closed and DAD—which had also nurtured Mad Cow Theatre and started the Theater Garage next to the T.D. Waterhouse Center—had begun to draw criticism for a perceived lack of focus. In fact, even some high-profile supporters admitted that the organization had drifted as downtown real estate had soared out of reach for most small arts venues. Was a true downtown arts district even possible?

Due to budget constraints, Hood’s successor, Buddy Dyer, had to cut the position of Brenda Robinson, who had been Hood’s executive director of arts and culture—and DAD’s most tireless advocate in City Hall. (Dyer, as city budgetary woes eased, would become a strong ally of DAD.)

Yet, perhaps OVAL’s closure was a blessing in disguise. DAD quickly sublet the 20,000-square-foot building from the city and—using private donations, city and county funds, and in-kind services from contractors and subcontractors—remodeled the building to the tune of $1.5 million and opened the CityArts Factory.

The facility—modeled after the much larger Torpedo Factory Arts Center in Alexandria, Virginia—had five galleries and a glassblowing studio on the first floor, and a multipurpose space on the second floor later occupied by SAK Comedy Lab. Most importantly, though, DAD now had a tangible, public-facing presence in the central business district—which its boosters had been pressing for.

The organization’s headquarters remained in that location until 2018, when philanthropist and art-lover Ford Kiene—who knew that his time was short due to failing health—donated downtown’s oldest commercial structure, the Rogers Building, to the city. There was only one stipulation: that the building be used for an arts-related purpose for at least 20 years.

The emerald-hued Queen Anne-style landmark—now known as the Rogers-Kiene Building—was constructed in 1886 by settler Gordon Rogers as a private club for Orlando’s English Colony, a group of immigrants who crossed the pond to become ranchers and citrus growers. Kiene, who had restored the building, had been its owner since the 1990s and had conducted a meticulous restoration.

Today the building at the corner of Magnolia Avenue and Pine Street is home to DAD and CityArts, the organization’s flagship venue with five galleries, an in-house café and a second-floor multiuse venue. There are year-round open calls for artists who wish to stage exhibitions, and the organization is proud of its commitment to emerging and offbeat artists.

In 2024, DAD renovated an adjacent outdoor space (more precisely, an alley) using materials salvaged from the Church Street Ballroom, which was part of the lavish downtown entertainment district known as Church Street Station. The project, called Fordify the Arts Courtyard, was a tribute to Kiene, who died in 2022.

DAD—which operates on a $1 million annual budget—has thrived in recent years, perhaps in part because its uber-cool location emits such happy, creative vibes and its events are always crowd-pleasers.

“Our events have really brought people downtown,” says attorney Jim Lussier, a founding board member who had also been the volunteer president of OVAL. “I think we’ve taken them to the next level.”

For example, CityArts is the scene of a monthly 3rd Thursday Gallery Hop, which features art activations, live performances, history exhibitions and more; and Art After Dark, which targets young professionals with a silent auction, complimentary craft cocktails and gourmet lite bites.

Also monthly is a musical event, The In-Between Series; and a spoken-word event, The Story Club. And nobody wants to miss the annual (and over-the-top) Dia De Los Muertos & Monster Party—which colorfully (and spookily) celebrates a holiday that originated in Mexico.

“Our purpose remains to provide a home for artists to meet and show and sell their work, and to get more arts programming downtown,” says Barbara Hartley, executive director of DAD since 2011. Hartley, a former marketing executive who earned an MBA from the Crummer Graduate School of Business at Rollins College, also notes that the arts are a major driver of economic growth.

But it’s the impact that DAD and CityArts has had on individual artists that is most compelling. Abstract artist Paul Michael Columbus notes that CityArts hosted the first indoor exhibition of his work and that of his wife, Jennifer, an abstract expressionist. Both have since seen their careers flourish with exhibitions around the state.

“Since then, they’ve continued to be a vital part of our growth and development as artists,” says Columbus. “We’re deeply honored to support the DAD and CityArts, both of which have been central to our journeys as artists and to the creative community.”

So, is it true that a downtown arts district is as pie-in-the-sky now as it may have seemed several decades ago? Anyone who still thinks that’s the case clearly hasn’t been paying attention.

In addition to what CityArts itself has to offer, there are usually assorted public-art projects underway and free arts and cultural events of all kinds sponsored by DTOLive! (a partnership between the City of Orlando’s Downtown Development Board and United Arts of Central Florida).

And, of course, you’ve got Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts—which has more venues still to come—and the ongoing development of Craig Ustler’s 68-acre Creative Village on the site of the former Amway Arena, which will ultimately include many arts-related components and is already home to the downtown campuses of UCF and Valencia College.

Plus, there are hip and artsy designated districts near the downtown core, including the Ivanhoe District, the Milk District, the Mills 50 District and the SoDo District—all of which are fun and eclectic and bustling with creative energy.

Anyway, you get the picture. The Downtown Arts District and CityArts are located at 39 South Magnolia Avenue, Orlando. For more information, call 407.648.7060 or visit downtownartsdistrict.com.

15

Central Florida Community Arts

Justin Muchoney is executive director of CFCArts—and an original co-founder—who also conducts the organization’s Symphony Orchestra. But, despite the plethora of choirs and orchestras, it’s not all about music. Among CFCArts’ most highly regarded programs is Narrators, an acting troupe for older adults designed to foster cognitive health.

Joshua Vickery and Justin Muchoney, both creative, career-long cast members who worked in multiple entertainment-related capacities at Walt Disney World, happened to be “casting directors” (not judges, since nobody in the Magic Kingdom is judged) at the American Idol Experience at Disney’s Hollywood Studios.

As with the ABC series, the competition invited singers to perform before a team of, well, casting directors (which included no corollary to the sometimes-caustic Simon Cowell) as a raucous live audience watched and ultimately picked their favorites.

Both men noticed that many performers were very good—which wasn’t a surprise, since the region is a hotbed of talent. But they were surprised that many of the contestants felt isolated in transient Central Florida, where everyone comes from somewhere else and it can be difficult to find groups of kindred spirits.

“They didn’t feel connected to where they were,” says Muchoney, now executive director of Central Florida Community Arts (CFCArts), which started out as an ad hoc community choir 15 years ago. And what a Rock ‘n’ Roller Coaster ride it has been—with the trajectory mostly up.

Today, CFCArts is a multifaceted arts organization whose mission is “to serve and build community through the arts. We connect, inspire, and strengthen by creating experiences that unite people and transform lives.”

Recalls Muchoney of his time at the American Idol Experience: “We often had conversations with the contestants. We’d ask people, ‘Where do you sing?’ They’d say, ‘Oh, just in my car or in the shower.’ They were missing something in their lives.

So, Vickery—whom Muchoney describes as “a force of nature with a fierce work ethic”—proposed a now-legendary “garage meeting” in summer 2010 at his home to discuss solutions. “I was one of those people Joshua wanted to help,” adds Muchoney. “I had just moved to the area myself.”

Attending, in addition to Vickery and Muchoney, were about 15 people. Among them was Brandon Fender, a choral singer and director, and Katherine “Kat” Gray, a high-school English teacher and a director of musicals for children. These big-hearted artists are considered to be the founders of what would become the nonprofit CFCArts.

“We never had any intention of creating anything of the scope that would come later,” says Vickery, the organization’s first executive director who since 2021 has been CEO of Washington, D.C-based Encore Creativity, a nonprofit that offers choir and music programs to older adults across the country. “Our initial idea was to start a choir that everyone could participate in. Service was the foundation.”

Vickery proposed that everyone contact someone that they knew—in person, via email or through social media—and invite them to join an inclusive, all-volunteer choir that would sing simply for the joy of singing and sharing music with community groups—especially nonprofits.

Everyone, it seemed, was on board. The first official concert of the CFCArts Community Choir, held in May 2011, was a performance called Salute to American Heroes held at Orlando Baptist Church. The choir numbered a surprising 140 singers. That event was followed in December by a holiday extravaganza at Northland Church in Longwood.

Soon the organization began to expand rapidly as founders identified still more needs and sought to fill them. You had to be 18 or older to sing in the Community Choir. So, what about kids? Ask and ye shall receive: The following year brought the debut of the Youth Theater Program.

And there was more on the way: In 2012, the Symphony Orchestra, and in 2016, the Big Band. Then, perhaps most ambitiously, in 2018 came the School of Arts & Health, which offered programs aimed at improving well-being through participation in arts activities.

Among those programs was Narrators, an acting troupe for older adults designed to foster cognitive health; Musical Minds, a singalong group for adults in the early stages of dementia; Music Therapy, which forged partnerships with senior-care organizations; and UpBeat! Theatre Troupe, which offered performing opportunities for youth and young adults who are neurodivergent.

Maitland resident Candy Dawson, a retired teacher turned author, says she never dared to try acting and figured, at age 75, it was too late to start. But she has loved being involved with Narrators, in which weekly two-hour sessions encompass senior-friendly improv and theater games as well as rehearsals for upcoming performances.

“Classes are filled with laughter and activities that warm up both body and brain,” says Dawson. “Just picture us, ages 55 to 90, passing around an imaginary pair of jeans that are way too tight and trying every trick in the book to wiggle into them.”

Such initiatives got noticed. In 2020, UpBeat! notched the Hamilton International Arts in Health Award for Innovation through the National Organization of Arts in Health (NOAH). In 2024, the program also earned a community impact grant from the Doug Flutie Jr. Foundation for Autism.

That same year, CFCArts won an overall recognition from the Music Cities Awards—a global organization that recognizes transformative uses of music—for its innovative arts and wellness programs. Such laudable zeal, however, may have caused the fast-growing, big-hearted group to get ahead of its skis.

Says Muchoney: “We would just see a need and say, ‘Hey, great! We’re here.’” That is, until they almost weren’t here. In July 2024, CFCArts experienced a cash crunch, forcing it to shed some programs and lay off four staffers. An independent forensic audit was commissioned and a panel of experts was enlisted to help right the fiscal ship.

There was also a leadership shuffle. Muchoney, who had been music director and conductor, became interim executive director upon the departure of Terrance Hunter, who had been vice president for operations and education but said he lacked the financial expertise required for the top job. (Muchoney was named permanent executive director in April 2025.)

Chad Faulkenberry, current chairman of the board of directors and a founding board member, says the organization has indeed bounced back: “The team, especially the staff, has done a phenomenal job tightening up our mission, and we’ve enjoyed a good turnaround.”

(Faulkenberry, a financial advisor and managing director of Journey Wealth Management, also plays drums in the CFCArts Big Band.)

Multitudes are glad that it all worked out. Last year, some 1,100 people participated in CFCArts programs that cumulatively attracted at least 21,500 attendees. Generally, with exceptions for some lead roles, auditions aren’t required for performers. There’s only a small membership fee, for which scholarships are available. Financial assistance is also available for popular tuition-based summer programming.

Now operating from headquarters at the First Congregational Church of Winter Park—with a $1.8 million budget, eight full-time employees and 20 major productions scheduled—CFCArts has some exciting things planned in conjunction with its 15th anniversary year.

Although all concerts and events will acknowledge the milestone, Dreaming Together: Greatest Hits from 15 Years of Community—slated for Friday and Saturday, November 14 and 15 at Northland Church—will be specifically linked to the celebration.

The musical mashup will feature the 300-member Community Choir accompanied by a 50-member ensemble of players who’ll perform a genre-defying program that will include such diverse selections as “O Fortuna,” “Let the Sun Shine In” and “Over the Rainbow.” The concerts will be at 7:30 p.m. on Friday, and at 2 and 7:30 p.m. on Saturday.

Says Muchoney, who’ll also help direct: “This concert is more than a look back—it’s a joyful leap forward, together. You’ll experience the heart, harmony and hope that have shaped a decade and a half of connection through the arts.”

10

Opera Orlando

Gabriel Preisser, general director, and his brother Grant Preisser, artistic director, have made opera among the hottest tickets in town over the past decade. Gabriel, a veteran performer, also appears in some of the company’s productions. Earlier this year, for example, he played the King in Massenet’s Cendrillon alongside tenor Zhengyi Bai as Prince Charming. | Courtesy Opera Orlando

Garbriel Preisser occupied two seemingly disparate planets in the usually stratified universe of public education. At West Orange High School—where his dad, Gary, was principal—the teenager was a football player who would sing the national anthem prior to games in his pads and eagerly participate in the school’s musical productions.

That made sense because the elder Preisser’s storied career also included stints as a football coach at Apopka, Bishop Moore, Dr. Phillips and Edgewater. But Gerry, mother of the couple’s five boys and one girl, insisted that all the kids take piano lessons and sing in church.

“Singing came naturally to me,” says the younger Preisser, who was an all-county offensive lineman. “But I always thought I would go to college at Florida State and walk on and play football. Luckily, I got a full ride for the music program and didn’t get killed.”

Lucky, indeed, for both Preisser and for opera fans in Central Florida. Today, as Opera Orlando marks its 10th year, the company has reached new heights under Preisser, the general director and a frequent performer, and his older brother Grant, previously the creative director and now the company’s artistic director.

It has certainly taken some doing. Opera as a genre has endured a decades-long roller-coaster ride in Orlando that began in 1958 with the Junior League of Orlando’s Gala Evening of Opera at the Orlando Municipal Auditorium (later the Bob Carr Theater).

For that auspicious event, four stars of New York’s Metropolitan Opera—soprano Lisa Della Casa, mezzo-soprano Elana Nikoliadi, tenor Richard Tucker and baritone Robert Merrill—appeared with the Florida Symphony Orchestra in a concert that the Orlando Sentinel called “one of the biggest musical events in the history of Central Florida.”

Tucker returned in 1963 to star in a fully staged production of La Bohème. Then, following a lull, the Junior League passed the proverbial baton to the new Orlando Opera Guild of the Florida Symphony Orchestra.

In 1974, the guild presented a then-unknown Jessye Norman singing the lead in Aida. It was considered groundbreaking at the time to showcase an operatic performance by an African American. It seemed, after such a string of notable successes, that there really was an audience—and a sophisticated one, at that—for opera in Central Florida.

So, in 1990, Orlando Opera, now a separate nonprofit, became a professional company for the first time. Under Robert Swedberg, general director, it staged some 80 productions, concerts and recitals over a span of 17 years, and engaged still more marquee names—including Cecilia

Bartoli, Placido Domingo, Jerry Hadley, Same Ramey and Denyce Graves.

Swedberg resigned abruptly in 2007, but Orlando Opera nonetheless celebrated its 50th anniversary with a fully staged version of Don Giovanni, which was reset in New Orleans and starred Peter Edelman and Inna Dukach. Yet, all was not well. During the Great Recession of 2008, which strangled fundraising and slowed ticket sales, the company’s structural weaknesses were laid bare.

After operating at a six-figure deficit for years, Orlando Opera suspended operations in 2009. To fill the void, the Orlando Philharmonic Orchestra (which was formed in 1993 following the dissolution of the Florida Symphony Orchestra) stepped up and began to offer semi-staged versions of operas as part of its regular season in the Bob Carr Theater.

First up was Carmen and Porgy and Bess—with free tickets for those who had paid for Orlando Opera’s doomed 2009-2010 season—followed by La Bohème in 2011 and Rigoletto in 2012. “We can’t afford to lose a single person in this community who’s interested in the arts,” said United Arts of Central Florida’s then-president Margot Knight to the Orlando Sentinel.

The Phil’s efforts, although appreciated and well-reviewed, were really rarified concerts, not full-fledged, over-the-top operas. Considering recent history, however, no one was eager to invest in extravaganzas. As the 18th-century French dramatist Molière put it: “Of all the noises known to man, opera is the most expensive.”

The best way to come back, boosters believed, was to start small and rebuild an audience for opera in its intended form. So Florida Opera Theatre, the predecessor of Orlando Opera (and later Opera Orlando), was organized within months of the prior company’s collapse by several dozen determined (and undaunted) volunteers whose passion compensated for their inexperience.

Orlando resident Ann Fox, president of the Opera Guild when Orlando Opera disbanded, became Florida Opera Theatre’s first president, and helmed it though an organizational period that included applying for and receiving nonprofit status. After her term was complete, Fox stepped aside and was followed by Maitland resident Judy Lee, who would go on to serve five terms.

“We didn’t do any full operas for several years,” says Lee, whose group initially helped to support opera concerts from the Phil. “We couldn’t afford operas. And because of what had happened [with Orlando Opera], we were very careful. We knew that the first time we couldn’t pay a bill, we were done.”

Still, the volunteer-run Florida Opera Theatre began to gain trust and gather momentum. When the company decided that it was ready to launch fully staged productions, members foraged through their garages and closets for costumes and stage props. They also dipped into their personal bank accounts to hire singers, directors and accompanists—most of whom agreed to work for less than their accustomed fees on behalf of the cause.

And because the company couldn’t afford to rent theaters for every production, members also had to scout out inexpensive—and often ingenious—locations. In fact, its first full-scale opera, Menotti’s The Medium, which featured Vero Beach-based soprano Susan Neves, was performed in December 2011 at the Winter Park home of Steve and Kathy Miller.

(Steve Miller, cofounder of Sawtek Inc., a manufacturer of custom-designed electronic components, died in 2025. Kathy Miller is a classically trained vocalist who has sung in the chorus for several productions by Orlando Opera and remains a major supporter of Opera Orlando.)

Subsequently, the upstart outfit presented The Telephone, a one-act comic opera by Gian Carlo Menotti, at the Germaine Marvel Building near the Maitland Art Center and (appropriately) its adjacent Telephone Museum. The opera was paired with A Musical Revue of Ringing Proportions, in which several cast members performed a selection of arias.

An opera-singing troupe also startled a few lounge lizards and drew double-takes from moviegoers by creating a pop-up, open-air concert at Eden Bar outside Enzian, the art-house cinema in Maitland. (They sang—what else?—“Drink, Drink, Drink” from The Student Prince.)

In March 2015, when it came time to debut in the just-completed Dr. Phillips Center for the Performing Arts, the company presented Mozart’s comic opera Così Fan Tutte in the cozy confines of the 300-seat Alexis & Jim Pugh Theater with a chamber orchestra of musicians from the Phil.

After years of performances in unusual spaces, Lee considered the well-received, two-show stand in a real theater to be a coming-out party. “I won’t say none of us knew anything about running an opera,” says Lee. “We had some board members from the previous company who were knowledgeable. But I will say none of us were music majors.”

Who, then, could take this grassroots effort to the next level? Well, as fate would have it, Preisser—the erstwhile football player-turned-performer—had earned not a concussion (or worse) but a degree in vocal performance and commercial music from FSU and a master’s degree in music from the University of Houston.

Over the course of his career in opera and musical theater, the charismatic baritone with leading-man looks had notched more than 40 roles—ranging from the title part in Sweeney Todd to Prof. Harold Hill in The Music Man—with companies that included, among many others, Helena Symphony, Colorado Symphony, Minnesota Opera and Opera Philadelphia.

He had married his high school sweetheart, Christina, a nurse, who traveled to gigs with him for the first several years before they decided to begin a family and chose to settle back home in Orlando. (The Preissers have two children: Grayson, 11, and Cora, 8.)

Preisser had been hired by Florida Opera Theatre several times as a performer and attended board meetings as an adviser. Perhaps, he recalls jokingly, “I spoke up too much.” Whatever the case, he was soon named executive and artistic director (now general director). Perfect! A permanent opera job that required no accumulation of frequent flyer miles.

Immediately, Preisser recommended rebranding the company as Opera Orlando, a change that was announced in January 2016. Grant, who also attended FSU and majored in voice, joined the newly energized company in 2017 and brought with him skills that both mirrored and complemented those of his brother.

Grant’s impressive resumé includes a master’s degree (one of three advanced degrees) in interior design as well as various executive positions at the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD), including helping to open and serving as dean of the college’s campus in Hong Kong. He has also been a performer, a director, and a sought-after expert in technical theater and production design.

The rest, of course, is history still in the making. Today, with a $3.1 million annual budget, Opera Orlando has a three-show Opera on the MainStage series that typically draws audiences of 1,000 or more per performance to Steinmetz Hall at Dr. Phillips Center. (This season will conclude with a separately ticketed “season extra” at Steinmetz Hall—a one-night-only concert called A Decade of Divas—in May.)

It also presents a three-concert Summer Series at the University Club in Winter Park, on-site operas at unexpected locations, a touring opera in schools and community venues, and multiple special events and educational programs throughout the season. Last year, such programs reached 100,000 people for the first time in the company’s history.

Best of all, Opera Orlando operates in the black. With an eye toward remaining fiscally solid, an endowment fund has been established with a $1 million gift from philanthropist and opera-lover Helen Hall Leon. That gift served as a catalyst for other major contributions, bequests and pledges to the fund, which now totals more than $3 million with a goal of reaching $10 million.

And the company has moved to a larger space in west Orlando, thanks in large part to a $125,000 grant from Edyth Bush Charitable Foundation, based in Winter Park, which will support expansion of the scene shop plus the addition of a full-time marketing director.

Whew! Now, after all that dramatic backstory, how about some music? The 2025–26 season will kick off with Puccini’s La Bohème—directed by Grant Preisser—on Friday, October 3,

at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday, October 5, at 2 p.m. The setting will be Shanghai in the 1930s and most cast members will be Asian American, including South Korea-born baritone Seunghyeon Baek as Marcello.

“Gabe and Grant know opera very well, and since they are artists themselves, they know how to collaborate with the artists who are in their productions,” says Baek. “And Steinmetz Hall is beautiful. I love to perform there because the sound is excellent.”

Also during the anniversary season, All Is Calm—the poignant story of an unlikely night of camaraderie, music and peace between combatants during World War I—will be presented this year at Orlando Family Stage. There’ll be four free performances on Friday, December 12, at 7:30 p.m.; Saturday, December 13, at 2 and 7:30 p.m.; and Sunday, December 14, at 2 p.m.

But wait, there’s more! the company plans to reprise The Secret River—an Opera Orlando-commissioned work based on a children’s book by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings—in partnership with Orange County Schools at Mead Botanical Garden’s Grove Amphitheater in Winter Park on Friday and Saturday, March 6 and 7, 2026, with both performances at 7:30 p.m.

And how about a party in the meantime? A new signature event will debut this season called the Operazzi Bash, a fundraiser for the company’s educational programs—including the apprentice artist and studio artist programs as well as the Opera Orlando Youth Company.

This immersive and interactive mashup of pop and opera is slated for Saturday, October 25, at 6 p.m. at the Grand Bohemian Hotel in Downtown Orlando. The hotel, not coincidentally, was the site of the company’s first fundraising gala a decade ago.

“Opera is just musical theater on steroids,” says Preisser on the company’s expansive (and sometimes playful) approach to a genre that some still view as stuffy. “We don’t do museum opera.” For more information about season tickets as well as the gala and other events, visit drphillipscenter.org or operaorlando.org. You can find a 10th anniversary video here.